- Home

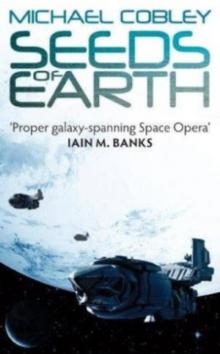

- Seeds of Earth

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1 Page 7

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1 Read online

Page 7

seed husks which grew only at the highest places of

Segrana. Bonded to a branch or trunk near a Uvovo

town or village, they served as a Listener shrine, a

refuge for private meditation, as well as the centrepiece

of public ceremonies. An outcast like Pgal could

become a full member of either Uvovo clade by taking

a vigil in a vudron, but only if invited by a Listener.

Like Weynl.

'I am happy for you, Pgal,' she said. 'Thank you for

all your help, and go in peace.'

The herder smiled, bowed his head, then steered his

trictra down from the platform and along the meshed

vines.

And thank you, Weynl, she thought, watching him

leave. You really don't want me going near the forest

floor, do you? Well, let's see what my wee camera spot-

ted, shall we}

She glanced around her to make sure she was alone,

then took out the cam, fitted a viewing ocle to the

output, pressed Play and held it up to her eye.

And saw . . . only flickering confusion. The timer

readout was the same as when she got the trip signal,

but the recording was a blurred, stuttering mess. She

ran it again and again, trying to find more than just

hints of a dark form that might have been a creature,

or shaky stick-like things that might have been

limbs . . .

She lowered the cam and sagged against one of the

platform's heavy, woven hawsers. She suddenly felt

weary, as if the recording had knocked the vitality out of

her. It had been such a waste, scrounging the cam from

Lyssa Devlin's team over at Skygarden, skulking down

there to plant it then retrieving it, all a waste of time and

effort. It might be possible to process and filter the

image data, but only the Institute office at Viridian

Station would have that kind of equipment and anyway,

how could she explain how she obtained such a record-

ing without admitting to multiple violations of the

Respect Accords?

Disconsolate, she put the minicam away in her

pouch, slung the baggy robe over one shoulder and

climbed the branch stairway that led to the Human

enclave. Halfway up, the stairs trembled a little under-

foot as someone came hurrying across a flimsy-looking

gantry from another platform. It was Tomas Villon, one

of her team's tech assistants. His features were ffusl ed

and excited as he raised a hand in greeting and :al ed

out.

'Doctor Macreadie,' he said. 'Have you heard the

news?'

'No - what news?'

He grinned. 'The president announced it in his wide-

cast this morning, and the channel heads have been

talking about nothing else . . .'

'Sorry, Tomas, but I've been working hard, and Ive

been away all morning. What's happened?'

Clearly delighted at being able to let her in on the

story, he cleared his throat. 'Well, as I said, the president

came on the vee this morning to tell us that the

Hammergard government has been in contact with a

ship from Earth!'

First she gasped in disbelief, then started talking,

almost tripping over her own words.

'But that's . . . incredible! You're sure, Tom as,

absolutely sure?'

'It's the honest truth, Catriona, I swear! The ship is

called the Heracles and it's entering orbit around Dan en

right this moment. Look, there's a vee-panel up in the

mess hut which is where the rest'll be, watching the live

relay from Port Gagarin.'

A web-tethered flock of membrane insectoids drifted

past on a warm updraught as they hastened up to the

enclave buildings. Catriona grinned while trying to

think through the giddy thrill she was feeling.

'It's unbelievable,' she said. 'I never thought I'd live to

see this - I wonder what they'll be like? You remember

that play by Fergus Brandon?'

'The Lifeline?" He chuckled. 'I doubt that any would-

be colonists will be queueing to come out here. Said as

much to Greg Cameron earlier.'

'Greg?' she said, trying to sound vaguely disinter-

ested. 'What were you calling him about?'

'Neh, he called us to gossip about the announcement.

We gabbed on about it and the Brandon play came up.

Yah, he's just as excited about it as everyone.'

Of course, Catriona thought. Those two were good

friends at college, so it's no surprise that he would call. She

felt a small shiver go through her. I wonder how he's been

since he came back .. . but why should I wonder? He's

just another man who's got better things to do than .. .

She had only met him a few times, ever since she'd

suggested the link between the proportions of the temple

on Giant's Shoulder and the physique of the Uvovo, and

she had hoped that their professional friendship might

become something deeper. And then he gave up every-

thing and moved away up north to Trond to get

married, settle down and have kids, apparently - only to

return several months later, alone. Hopes which had col-

lapsed rose again, but tempered this time with a dash of

realism and caution.

And now she was resolved not to let Greg Cameron

or her failed minicam experiment dilute her excitement

at Tomas's news.

'Right, Tomas,' she said with a determined laugh as

they came up to the mess hut. 'Let's see if we can get a

good seat!'

6

ROBERT

On board the Earthsphere cruiser Heracles, in the

largest of its three staterooms, Ambassador Robert

Horst was indulging in the archaic practice of packing

luggage.

'I don't know why you don't ask the room to do it for

you,' said Harry, his AI companion.

'But the room doesn't know what I need to take with

me.'

'The room has access to your sartorial profile, as well

as Darien's styles and customs, such as they are. So

where's the problem?'

'The room can't know what I need,' Robert said,

smiling as he placed a semi-formal tunic into his parti-

tioned valise. 'Because I don't know myself. Or rather,

when I see it I'll know that I need it.'

Harry smiled and shook his head. In Robert's field of

vision, Harry seemed to be standing over by the state-

room's centrepiece, a sleek porcelain and perspex

column with a holobase in each of its five faces. He

resembled a young man dressed in an immaculate but

outmoded black suit, his round features displaying a

perpetual amusement and a hint of cynicism. Robert

had chosen to model his companion upon the main

character from an American black-and-white flat-movie

from the mid-twentieth century, whose storyline dealt

with postwar intrigue and betrayal. Orson Welles's por-

trayal of the mercurial Harry Lime had captivated the

young Robert Horst, and after deciding on his compan-

ion's form he had also resolved that he would appear in

<

br /> monochrome. After all, he was the only one who would

see it.

'I'm not sure that the personal touch will be helpfu ,'

Harry said. 'After 150 years of isolation and resource

scarcity, social fashions are bound to be a little rustic'

'My God, Harry, you're a snob.'

'Not at all. I just feel sure that these poor, Earth-

hungry colonists will want an ambassador from the auld

country to look the part.'

Robert wagged a finger. 'What, play the lofty aristo

come to dispense wisdom to the local yokels? Sorry,

no - that's the Sendruka approach, not mine.'

'Shame on you, Robert, for denigrating the high

ideals of our allies in the cause of peace and justice,'

Llarry said, adopting a stance of mock grandeur fol-

lowed by a sly grin. 'Besides, your honoured Senclruka

colleague Kuros and his Ezgara goons are just along the

corridor. Who knows how many spymotes are drifting

around the ship by now, listening to our every word?"

'Not with the new antisurveillance systems the

Earthsphere Navy brought in after the Freya incident,'

Robert said, selecting from a small open section of the

storage wall a pair of Russian leather gloves, a couple of

plaid kerchiefs and a carved wooden ring. 'I'm more

concerned about why they're here at all.'

The Heracles had been en route to the Huvuun

Deepzone when new orders came through to divert to

Chasulon, the capital world of Broltur, and take on

board the honoured High Monitor Utavess Kuros and

his unspecified personal guard. Which turned out to be

eight Ezgara commandos, four-armed biped soldiers

with a fearsome reputation, who wore all-enclosing,

steel-blue body-armour and never revealed their faces.

But Kuros and his guards were to be accorded every

courtesy, since they were there at the personal request of

Earthsphere President Erica Castiglione, apparently in a

dual capacity: as Alliance advisers, and as observers on

behalf of the Brolturan government.

Personal request*, he thought. I bet it was more like a

demand and Erica was on the receiving end of it.

T don't imagine that there's much to be anxious

about,' Harry said, resting his foot on the edge of a low

table. 'The Hegemony thinks that it has to keep tabs on

every political event otherwise things might fall apart,

the centre cannot hold and so on. Whereas things would

probably proceed quite normally if Hegemony attention

was elsewhere.'

'Harry, for you that's practically heresy.'

'I know. I blame it on prolonged exposure to the life

and works of Robert Horst! Anyway, it'll be politics on

a rather lesser scale for you in the weeks ahead.'

'True, but it could turn out to be quite productive.

One of the files sent from President Sundstrom's office

gave an interesting summary of their resource manage-

ment and extraction policies . . .'

'Ah, you mean these sifter roots that they got from

the Uvovo?' Harry chuckled. 'Ingenious way of getting

hold of pure elements, for a pre-nanofac society

Properly adapted, they could be put to use in other or -

texts, like hardvac prospecting for example. Or even

licensed out to cultures that prohibit nano applications.'

Robert shrugged. 'That sounds possible. I'm more

interested in the relations between our people and the

Uvovo, not to mention the colony's inner politics.'

'Well, for a small colony they've had a somewhat

chequered history. Problems with a shipboard AI that

went rogue, then a very tough first fifty years, expansion

problems, lack of resources, then contact with these

Uvovo sentients and an abortive civil war which exac-

erbated some already prickly divisions. But it's this Al

taboo that could pose difficulties. You should read some

of their novels and plays - artificial intelligences come

across like the rampaging death machines of the

Commodity Age. I find it positively insulting. What's

more, every year they celebrate the trashing of that poor,

dumb AI. Founders' Victory Day, they call it.'

'I agree, it's a problem, but I'm going to wait until

I've experienced Darien culture first-hand before con-

sidering solutions.' Robert parted another tall section of

the wall and touch-opened the units within. 'It's a matter

of how to establish the notion of everyday, common -

place, benevolent AIs . . .'

As he reached in, almost absentmindedly, and pulled

out one of the shallow drawers, he stopped and stared in

dread at the palm-sized object it contained.

'Ah, so that's where the room put it,' Harry mur-

mured. T can have it stored somewhere else if you like.'

'No, no, it's all right,' Robert said. T can't keep on

avoiding it. . .'

It was an intersim, a flat octagonal pad, mainly pale

blue in colour with ochre trim around the readout and

fingertip controls on one of the sides. The projection

plate on top was like dark, smoky glass within which

clusters of faceted emitters were just visible. It had a

certain solidity to it, like the weight of compacted tech-

nology, or the weight of memory.

It was now almost a year since his daughter Rosa

had died while on board the Pax Terra, z. refitted,

unarmed scoutship owned by the protest group Life and

Peace. The Pax Terra had been taking part in an

attempted blockade of a wayport on the Metraj border

from which Earthsphere and Sendruka Hegemony war-

ships were leaving for the Yamanon Domain. The

official version was that the protest boat was a sus-

pected bombship pursuing a collision course with a

Hegemony cruiser whose commander had no option but

to open fire. Initially Earthsphere government had made

mild objections, but soon dropped the matter.

Robert and his wife Giselle were distraught, and the

Diplomatic Service was thankfully swift to offer him

compassionate leave. But Robert was unable to stay at

home in Bonn and mourn - he had to know the truth

about Rosa's death.

Sitting at the end of a blue settle, he held the interac-

tive sim in his hands and recalled the months spent

tracking down witnesses to the blockade incident and

speaking with her friends and colleagues at Life and

Peace. What he learned utterly contradicted the official

version of events, while confirming much of what he

knew about his daughter, about her intellect and wit,

and about her compassion and her willingness to put

herself on the line for what she believed in. Millions

had died when the Earthsphere-Hegemony coalition

invaded the Yamanon Domain and bombarded the Dol -

Das regime's key worlds. Rosa had called those deaths

an atrocity, a judgement he could no longer disagree

with.

'We taught her to love,' he once said in a message to

his wife during his travels, 'and she did what she did out

He was on Xasome in the Kingdom of Metraj, trying

to glean corroborating data from public archive reports,

when he received a package via the local Earthsphere

consulate. It was from Earth, from his wife, and accom -

panying it was a short note that read: 'Dearest, I have

found a way to bring the light back into our lives, and

now you have one too. With love and joy - Giselle.1

Thinking it to be some compendium of images and

other recordings from the family archive, Robert had

placed the intersim on a desk and switched it on. The

device had emitted three flashes, mapping the room, and

a moment later, abruptly, Rosa was standing then,

dressed in one of her favourite outdoor rigs, smiling at

him.

'Hi, Daddy!' she had said.

So brightly she spoke, so vibrant with that delighted

alertness of hers, that he almost said, 'Rosa! - you're

alive . . .'

But the words had choked in his throat as reason

took hold, and he had stared at the simulation of his

daughter in a wordless horror.

'Daddy, how are you?'

Unable to speak or look away, still he had reached

out deliberately, with all of his will, and switched the

device off. Looking at it now, resting on his palm, he

knew what had driven Giselle to have such a thing

made. He had understood and let the anger fade, know-

ing that part of the anger had been directed at his own

despairing need for Rosa not to be dead.

And yet . . . and yet he could not bring himself to

destroy the sim, or at least have its memory wiped, not

then and not now.

Then, reaching a decision, he slipped the intersim

into his jacket pocket, stood and resumed packing.

'Are you sure that's wise?' said Harry.

Robert smiled as he tucked away the last items of

clothing. 'You think I may be putting my negotiating

temperament and thus this assignment at risk?'

Harry assumed a look of mock surprise.

'What a hurtful interpretation of my genuine con-

cern. I merely suggest that leaving the damned thing

here would help your peace of mind.' He paused, face

becoming more serious. 'Robert, I think that you're

hurting yourself by taking it with you.'

Robert sighed. 'I appreciate the concern, Harry, truly.

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1