- Home

- Seeds of Earth

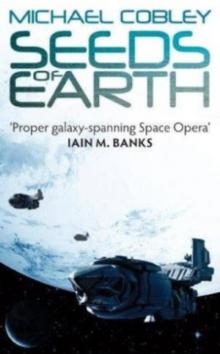

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1 Page 2

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1 Read online

Page 2

The Uvovo looked up and seemed to think for a

moment before his finely furred features broke into a

wide smile.

Friend-Gregori,' came his hollow, fluty voice.

'Whether I ride in a dirigible or make the shuttle journey

to our blessed Segrana, I am always amazed to discover

myself alive at the end!'

They laughed together as they continued down the

side of Giant's Shoulder. It was a cool, clammy night and

Greg wished he had worn something heavier than just a

work shirt.

'And you've still no idea why they're holding this

zinsilu at Ibsenskog?' Greg said. For the Uvovo, a zin-

silu was part life evaluation, part meditation. T mean,

the Listeners do have access to the government comnet

if they need to contact any of the seeders and schol-

ars .. .' Then something occurred to him. 'Here, they're

not going to reassign ye, are they? Chel, I won't be able

to manage both the dig and the daughter-forest reports

on my own! - I really need your help.'

'Do not worry, friend-Gregori,' said the Uvovo.

'Listener Weynl has always let it be known that my role

here is considered very important. Once this zinsilu is

concluded, I am sure that I will be returning without

delay.'

I hope you're right, Greg thought. The Institute isna

very forgiving when it comes to shortcomings and

unachieved goals.

'After all,' Chel went on, 'your Founders' Victory

celebrations are only a few days away and I want to

be here to observe all your ceremonies and rituals.'

Greg gave a wry half-grin. 'Aye . . . well, some of our

"rituals" can get a bit boisterous . . .'

By now the gravel path was levelling off as they

approached the zep station and overhead Greg could

hear the faint peeps of umisk lizards calling to each

other from their little lairs scattered across the sheer

face of Giant's Shoulder. The station was little more

than a buttressed platform with a couple of buiidb gs

and a five-yard-long covered gantry jutting straight out.

A government dirigible was moored there, a gently

swaying 50-footer consisting of two cylindrical gasbags

lashed together with taut webbing and an enclosed g< n-

dola hanging beneath. The skin of the inflatable sections

was made from a tough composite fabric, but exposure

to the elements and a number of patch repairs gave it a

ramshackle appearance, in common with most of the

workaday government zeplins. A light glowed in the

cockpit of the boatlike gondola, and the rear-facing,

three-bladed propeller turned lazily in the steady breeze

coming in from the sea.

Fredriksen, the station manager, waved from the

waiting-room door while a man in a green and grey

jumpsuit emerged from the gantry to meet them.

'Good day, good day,' he said, regarding first Greg

then the Uvovo. 'I am Pilot Yakov. If either of you is

Scholar Cheluvahar, I am ready to depart.'

T am Scholar Cheluvahar,' Chel said.

'Most excellent. I shall start the engine.' He nodded

at Greg then went back to the gantry, ducking as he

entered.

'Mind to send a message when you reach Ibsenskog,'

Greg told Chel. 'And don't worry about the flight - it'll

be over before you know it. . .'

'Ah, friend-Gregori - I am of the Warrior Uvovo.

Such tests are breath and life itself!'

Then with a smile he turned and hurried after the

pilot. A pure electric whine came from the gondola's aft

section, rising in pitch as the prop spun faster. Greg

heard the solid knock of wooden gears as the station

manager cranked in the gantry then triggered the moor-

ing cable releases. Suddenly free upon the air, the

dirigible swayed as it began drifting away, picking up

speed and banking away from the sheer face of Giant's

Shoulder. The trip down to Port Gagarin was only a

half-hour hop, after which Chel would catch a com-

mercial lifter bound for the Eastern Towns and the

daughter-forest Ibsenskog. Greg could not see his friend

at any of the gondola's opaque portholes but he waved

anyway for about a minute, then just stood watching the

zeplin's descent into the deepening dusk. Feeling a chill

in the air, he fastened some of his shirt buttons while

continuing to enjoy the peace. The zep station was

nearly 50 feet below the main dig site but it was still

some 300 feet above sea level. Giant's Shoulder itself

was an imposing spur jutting eastwards from a towering

massif known as the Kentigern Mountains, a raw

wilderness largely avoided by trappers and hunters,

although the Uvovo claimed to have explored a good

deal of it.

As the zeplin's running lamps receded, Greg took in

the panorama before him, the coastal plain stretching

several miles east to the darkening expanse of the

Korzybski Sea and the lights of towns scattered all

around its long western shore. Far off to the south was

the bright glitterglow of Hammergard, sitting astride a

land bridge separating Loch Morwen from the sea;

beyond the city, hidden by the misty murk of evening,

was a ragged coastline of sealochs and fjords where the

Eastern Towns nestled. South of them were hills and a

high valley cloaked by the daughter-forest Ibsenskog.

Before his standpoint were the jewelled clusters of Port

Gagarin, slightly to the south, High Lochiel a few miles

northwest, and Landfall, where the cannibalised hulk of

the old colonyship, the Hyperion, lay in the sad tran-

quillity of Membrance Vale. Then further north were

New Kelso, Engerhold, Laika, and the logging and

farmer settlements scattering north and west, while off

past the northeast horizon was Trond.

His mood darkened. Trond was the city he had left

just two short months ago, fleeing the trap of his disas-

trous cohabitance with Inga, a mistake whose wounds

were still raw. But before his thoughts could begin cir-

cling the pain of it, he stood straighter and breathed in

the cold air, determined not to dwell on bitterness and

regret. Instead, he turned his gaze southwards to see the

moonrise.

A curve of blue-green was gradually emerging from

behind the jagged peaks of the Hrothgar Range which

lined the horizon: Nivyesta, Darien's lush arboreal

moon, brimming with life and mystery, and home to the

Uvovo, wardens of the girdling forest they called

Segrana. Once, millennia ago, the greater part of their

arboreal civilisation had inhabited Darien, which they

called Umara, but some indeterminate catastrophe had

wiped out the planetary population, leaving those on

the moon alive but stranded.

On a clear night like this, the starmist in Darien's

upper atmosphere wreathed Nivyesta in a gauzy halo of

mingling colours like some fabulous eye staring down

on the little niche that

humans had made for themselves

on this alien world. It was a sight that never failed to

raise his spirits. But the night was growing chilly now, so

he buttoned his shirt to the neck and began retracing his

steps. He was halfway up the path when his comm

chimed. Digging it out of his shirt pocket he saw that it

was his elder brother and decided to answer.

'Hi, Ian - how're ye doing?' he said, walking on.

'Not so bad. Just back from manoeuvres and looking

forward to FV Day, chance to get a wee bit of R&R.

Yourself}'

Greg smiled. Ian was a part-time soldier with the

Darien Volunteer Corps and was never happier than

when he was marching across miles of sodden bog or

scaling basalt cliffs in the Hrothgars, apart from when

he was home with his wife and daughter.

'I'm settling in pretty well,' he said. 'Getting to grips

with all the details of the job, making sure that the var-

ious teams file their reports on something like a regular

schedule, that sort of thing.'

'But are you happy staying at the temple site, Greg? -

because you know that we've plenty of room here and I

know that you loved living in Hammergard, before the

whole Inga episode . . .'

Greg grinned.

'Honest, Ian, I'm fine right here. I love my work, the

surroundings are peaceful and the view is fantastic! I

appreciate the offer, big brother, but I'm where I want to

be.'

'S'okay, laddie, just making sure. Have you heard

from Ned since you got back, by the way}'

'Just a brief letter, which is okay. He's a busy doctor

these days . . .'

Ned, the third and youngest brother, was very poor at

keeping in touch, much to Ian's annoyance, which often

prompted Greg to defend him.

'Aye, right, busy. So - when are we likely to see ye

next} Can ye not come down for the celebrations ?'

'Sorry, Ian, I'm needed here, but I do have a meeting

scheduled at the Uminsky Institute in a fortnight - shall

we get together then?'

'That sounds great. Let me know nearer the time and

I'll make arrangements.'

They both said farewell and hung up. Greg strolled

leisurely on, smiling expectantly, keeping the comm in

his hand. As he walked he thought about the dig site up

on Giant's Shoulder, the many hours he'd spent

painstakingly uncovering this carven stela or that section

of intricately tiled floor, not to mention the countless

days devoted to cataloguing, dating, sample analysis and

correlation matching. Sometimes - well, a lot of the

time - it was a frustrating process, as there was nothing

to guide them in comprehending the meaning of the

site's layout and function. Even the Uvovo scholars were

at a loss, explaining that the working of stone was a skill

lost at the time of the War of the Long Night, one of the

darker episodes in Uvovo folklore.

Ten minutes later he was near the top of the path

when his comm chimed again, and without looking at

the display he brought it up and said:

'Hi, Mum.'

'Gregory, son, are you well?

'Mum, I'm fine, feeling okay and happy too, really ...'

'Yes, now that you're out of her clutches! But are

you not lonely up there amongst those cold stones and

only the little Uvovo to talk to?'

Greg held back the urge to sigh. In a way, she was

right - it was a secluded existence, living pretty much on

his own in one of the site cabins. There was a three-man

team of researchers from the university working on the

site's carvings, but they were all Russian and mostly

kept to themselves, as did the Uvovo teams who came in

from the outlying stations now and then. Some of the

Uvovo scholars he knew by name but only Chel had

become a friend.

'A bit of solitude is just what I need right now, Mum.

Beside, there's always people coming and going up here.'

'Mm-hmm. There were always people coming and

going here at the house when your father was a coun-

cilman, hut most of them I did not care for, as you might

recall'

'Oh, I remember, all right.'

Greg also remembered which ones stayed loyal when

his father fell ill with the tumour that eventually killed

him.

'As a matter of fact, I was discussing both you and

your father with your Uncle Theodor, who came by this

afternoon.''

Greg raised his eyebrows. Theodor Karlsson was his

mother's oldest brother and had earned himself a certain

notoriety and the nickname 'Black Theo' for his role in

the abortive Winter Coup twenty years ago. As a pun-

ishment he had been kept under house arrest on New

Kelso for twelve years, during which he fished, studied

military history and wrote, although on his release the

Hammergard government informed him that he was

forbidden to publish anything, fact or fiction, on pain of

bail suspension. For the last eight years he had tried his

hand at a variety of jobs, while keeping in occasional

contact with his sister, and Greg vaguely recalled that he

had somehow got involved with the Hyperion Data

Project. . .

'So what's Uncle Theo been saying?'

'Well, he has heard some news that will amaze you -

I can still scarcely believe it myself. It is going to change

everyone's life.'

'Don't tell me that he wants to overthrow the gov-

ernment again.'

'Please, Gregori, that is not even slightly funny ..."

'Sorry, Mum, sorry. Please, what did he say?'

From where he stood at the head of the path he had

a clear view of the dig, the square central building look-

ing bleached and grey in the glare of the nightlamps. As

Greg listened his expression went from puzzled to aston-

ished, and he let out an elated laugh as he looked up at

the stars. Then he got his mother to tell him again.

'Mum, you've got to be kidding me! . . .'

2

THEO

Theodor Karlsson had a spring in his step as he walked

up a private footpath towards the presidential villa. Tall,

thick bushes concealed it from inquisitive eyes, and

waist-high lantern posts shed pools of subdued radiance

all along its length. His long, heavy coat was three-quar-

ters fastened and his custom-soled shoes made little

noise on the tiled path. The villa grounds were dark and

still in the cool of the evening but Karlsson could almost

smell the weave of seamless security which enclosed the

place. There was a visible perimeter of patrols and cam-

eras down at the main wall and gate, and a pair of

guards at the side-door up ahead, but Theo knew that

the best security was seldom seen. The question that

loomed large in his mind, however, was who was it all

meant to keep out?

The guards, both wearing dark imager eye-pieces,

were muttering into collar mikes as he approached.

&nb

sp; 'Good evening, Major,' said one. 'If you could look

into the scanner with your right eye.'

He stepped up to the plain wooden door, followed

instructions, and moments later he heard several muf-

fled thuds. The door swung open. Inside he was met by

a composed, middle-aged woman who took his coat

then led him along a narrow, windowless corridor, past

a number of bland, pastoral paintings, then up a poorly

lit curve of steps to a landing with two doors. Without

pause she continued through the left one and Karlsson

found himself in a warm, carpeted study.

'Please make yourself comfortable, Major Karlsson.

The president will see you shortly'

'Thank you . . .' Theo began to say, but she ,vas

already leaving the room, closing the door behind her He

surveyed his surroundings, a medium-sized room with

well-stocked bookshelves, a log fire burning in the herrth,

and an ornate adjustable lamp hanging over a large cl zsi .

A ceiling-high rack of shelves partially concealed a second

door in one corner and a hand-eye security lock.

The belly of the beast, he thought. Or maybe the

lion's den.

It always felt like this whenever he had these meetings

with Sundstrom, no matter where they took place.

Which was why he had got into the habit of visiting his

sister, Solvjeg, shortly beforehand, just to quietly let her

know where he would be for the next few hours, with a

veiled hint as to whom he was meeting. Today, though,

she was full of eagerness to know if the rumours were

true, that there had been a signal from Earth.

Theo grinned, recalling the moment. The message

had apparently been received that morning, yet he had

heard it sixth-hand from an old friend in the Corps by

mid-afternoon, so it was no surprise that Solvjeg picked

it up from the old girls' network. Now it was evening

and the rumours were all over the colony. Even

Kirkland, the leader of the opposition, had issued a

statement, but so far there had been no official confir-

mation from either the council or the president's office.

A ship from Earthl he thought. So now we know

that the human race survived the Swarm War, but did

we beat them or did other survivors flee from Earth?

And what happened to the other two colonyships, the

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1

Michael Cobley - Humanity's Fire book 1